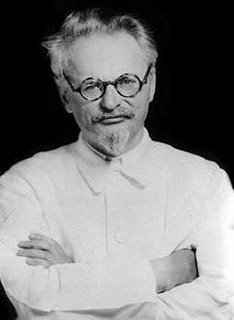

69th Anniversary of the Assassination of Leon Trotsky

[On this, the 69th anniversary of the assassination of Leon Trotsky, we are republishing the obituary delivered by James P. Cannon to the memorial meeting of the Socialist Workers Party held a week following the assassination. The text is courtesy of the Marxist Internet Archives:

http://www.marxists.org/archive/cannon/works/1940mom.htm]

James P. Cannon

To the memory of the Old Man (Trotsky Obituary)

This speech was delivered to the Leon Trotsky Memorial meeting held at the Diplomat Hotel in New York City on August 28, 1940.

It was first published in Socialist Appeal, September 7, 1940.

Comrade Trotsky's entire conscious life, from the time he entered the workers' movement in the provincial Russian town of Nikolayev at the age of eighteen up till the moment of his death in Mexico City forty-two years later, was completely dedicated to work and struggle for one central idea. He stood for the emancipation of the workers and all the oppressed people of the world, and the transformation of society from capitalism to socialism by means of a social revolution. In his conception, this liberating social revolution requires for success the leadership of a revolutionary political party of the workers' vanguard.

In his entire conscious life Comrade Trotsky never once diverged from that idea. He never doubted it, and never ceased to struggle for its realization. On his deathbed, in his last message to us, his disciples-his last testament-he proclaimed his confidence in his life-idea: "Tell our friends I am sure of the victory of the Fourth International - go forward!"

The whole world knows about his work and his testament. The cables of the press of the world have carried his last testament and made it known to the world's millions. And in the minds and hearts of all those throughout the world who grieve with us tonight one thought-one question-is uppermost: Will the movement which he created and inspired survive his death? Will his disciples be able to hold their ranks together, will they be able to carry out his testament and realize the emancipation of the oppressed through the victory of the Fourth International?

This speech was delivered to the Leon Trotsky Memorial meeting held at the Diplomat Hotel in New York City on August 28, 1940.

It was first published in Socialist Appeal, September 7, 1940.

Comrade Trotsky's entire conscious life, from the time he entered the workers' movement in the provincial Russian town of Nikolayev at the age of eighteen up till the moment of his death in Mexico City forty-two years later, was completely dedicated to work and struggle for one central idea. He stood for the emancipation of the workers and all the oppressed people of the world, and the transformation of society from capitalism to socialism by means of a social revolution. In his conception, this liberating social revolution requires for success the leadership of a revolutionary political party of the workers' vanguard.

In his entire conscious life Comrade Trotsky never once diverged from that idea. He never doubted it, and never ceased to struggle for its realization. On his deathbed, in his last message to us, his disciples-his last testament-he proclaimed his confidence in his life-idea: "Tell our friends I am sure of the victory of the Fourth International - go forward!"

The whole world knows about his work and his testament. The cables of the press of the world have carried his last testament and made it known to the world's millions. And in the minds and hearts of all those throughout the world who grieve with us tonight one thought-one question-is uppermost: Will the movement which he created and inspired survive his death? Will his disciples be able to hold their ranks together, will they be able to carry out his testament and realize the emancipation of the oppressed through the victory of the Fourth International?

Without the slightest hesitation we give an affirmative answer to this question. Those enemies who predict a collapse of Trotsky's movement without Trotsky, and those weak-willed friends who fear it, only show that they do not understand Trotsky, what he was, what he signified, and what he left behind. Never has a bereaved family been left such a rich heritage as that which Comrade Trotsky, like a provident father, has left to the family of the Fourth International as trustees for all progressive humanity. A great heritage of ideas he has left to us; ideas which shall chart the struggle toward the great free future of all mankind. The mighty ideas of Trotsky are our program and our banner. They are a clear guide to action in all the complexities of our epoch, and a constant reassurance that we are right and that our victory is inevitable.

Trotsky himself believed that ideas are the greatest power in the world. Their authors may be killed, but ideas, once promulgated, live their own life. If they are correct ideas, they make their way through all obstacles. This was the central, dominating concept of Comrade Trotsky's philosophy. He explained it to us many, many times. He once wrote: "It is not the party that makes the program [the idea]; it is the program that makes the party." In a personal letter to me, he once wrote: "We work with the most correct and powerful ideas in the world, with inadequate numerical forces and material means. But correct ideas, in the long run, always conquer and make available for themselves the necessary material means and forces."

Trotsky, a disciple of Marx, believed with Marx that "an idea, when it permeates the mass, becomes a material force." Believing that, Comrade Trotsky never doubted that his work would live after him. Believing that, he could proclaim on his deathbed his confidence in the future victory of the Fourth International which embodies his ideas. Those who doubt it do not know Trotsky.

Trotsky himself believed that his greatest significance, his greatest value, consisted not in his physical life, not in his epic deeds, which overshadow those of all heroic figures in history in their sweep and their grandeur-but in what he would leave behind him after the assassins had done their work. He knew that his doom was sealed, and he worked against time in order to leave everything possible to us, and through us to mankind. Throughout the eleven years of his last exile he chained himself to his desk like a galley slave and labored, as none of us knows how to labor, with such energy, such persistence and self-discipline, as only men of genius can labor. He worked against time to pour out through his pen the whole rich content of his mighty brain and preserve it in permanent written form for us, and for those who will come after us.

The whole Trotsky, like the whole Marx, is preserved in his books, his articles, and his letters. His voluminous correspondence, which contains some of his brightest thoughts and his most intimate personal feelings and sentiments, must now be collected and published. When that is done, when his letters are published alongside his books, his pamphlets, and his articles, we, and all those who join us in the liberation struggle of humanity, will still have our Old Man to help us.

He knew that the super-Borgia in the Kremlin, Cain-Stalin, who has destroyed the whole generation of the October Revolution, had marked him for assassination and would succeed sooner or later. That is why he worked so urgently. That is why he hastened to write out everything that was in his mind and get it down on paper in permanent form where nobody could destroy it.

Just the other night, I talked at the dinner table with one of the Old Man's faithful secretaries - a young comrade who had served him a long time and knew his personal life, as he lived it in his last years of exile, most intimately. I urged him to write his reminiscences without delay. I said: "We must all write everything we know about Trotsky. Everyone must record his recollections and his impressions. We must not forget that we moved in the orbit of the greatest figure of our time. Millions of people, generations yet to come, will be hungry for every scrap of information, every word, every impression that throws light on him, his ideas, his aims, and his personal life."

He answered: "I can write only about his personal qualities as I observed them; his methods of work, his humaneness, his generosity. But I can't write anything new about his ideas. They are already written. Everything he had to say, everything he had in his brain, is down on paper. He seemed to be determined to scoop down to the bottom of his mind, and take out everything and give it to the world in his writings. Very often, I remember, casual conversation on some subject would come up at the dinner table; an informal discussion would take place, and the Old Man would express some opinions new and fresh. Almost invariably the contributions of the dinner-table conversation would find expression a little later in a book, an article, or a letter."

They killed Trotsky not by one blow; not when this murderer, the agent of Stalin, drove the pickax through the back of his skull. That was only the final blow. They killed him by inches. They killed him many times. They killed him seven times when they killed his seven secretaries. They killed him four times when they killed his four children. They killed him when his old coworkers of the Russian Revolution were killed.

Yet he stood up to his tasks in spite of all that. Growing old and sick, he staggered through all these moral, emotional, and physical blows to complete his testament to humanity while he still had time. He gathered it all together-every thought, every idea, every lesson from his past experience-to lay up a literary treasure for us, a treasure that the moths and the rust cannot eat.

There was a profound difference between Trotsky and other great men of action and transitory political leaders who influenced great masses in their lifetime. The power of such people, almost all of them, was something personal, something incommunicable to others. Their influence did not survive their deaths. Just recall for a moment the great men of our generation or the generation just passed: Clemenceau, Hindenburg, Wilson, Theodore Roosevelt, Bryan. They had great masses following them and leaning upon them. But now they are dead; and all their influence died with them. Nothing remains but monuments and funeral eulogies. Nothing was distinctive about them but their personalities. They were opportunists, leaders for a day. They left no ideas to guide and inspire men when their bodies became dust, and their personalities became a memory.

Not so with Trotsky. Not so with him. He was different. He was also a great man of action, to be sure. His deeds are incorporated in the greatest revolution in the history of mankind. But, unlike the opportunists and leaders of a day, his deeds were inspired by great ideas, and these ideas still live. He not only made a revolution; he wrote its history and explained the basic laws which govern all revolutions. In his History of the Russian Revolution, which he considered his masterpiece, he gave us a guide for the making of new revolutions, or rather, for extending throughout the world the revolution that began in October 1917.

Trotsky, the great man of ideas, was himself the disciple of a still greater one-Marx. Trotsky did not originate or claim to originate the most fundamental ideas which he expounded. He built on the foundations laid by the great masons of the nineteenth century-Marx and Engels. In addition, he went through the great school of Lenin and learned from him. Trotsky's genius consisted in his complete assimilation of the ideas bequeathed by Marx, Engels, and Lenin. He mastered their method. He developed their ideas in modern conditions, and applied them in masterful fashion in the contemporary struggle of the proletariat. If you would understand Trotsky, you must know that he was a disciple of Marx, an orthodox Marxist. He fought under the banner of Marxism for forty-two years! During the last year of his life he laid everything else aside to fight a great political and theoretical battle in defence of Marxism in the ranks of the Fourth International! His very last article, which was left on his desk in unpolished form, the last article with which he occupied himself, was a defence of Marxism against contemporary revisionists and sceptics. The power of Trotsky, first of all and above all, was the power of Marxism.

Do you want a concrete illustration of the power of Marxist ideas? Just consider this: when Marx died in 1883, Trotsky was but four years old. Lenin was only fourteen. Neither could have known Marx, or anything about him. Yet both became great historical figures because of Marx, because Marx had circulated ideas in the world before they were born. Those ideas were living their own life. They shaped the lives of Lenin and Trotsky. Marx's ideas were with them and guided their every step when they made the greatest revolution in history.

So will the ideas of Trotsky, which are a development of the ideas of Marx, influence us, his disciples, who survive him today. They will shape the lives of far greater disciples who are yet to come, who do not yet know Trotsky's name. Some who are destined to be the greatest Trotskyists are playing in the schoolyards today. They will be nourished on Trotsky's ideas, as he and Lenin were nourished on the ideas of Marx and Engels.

Indeed, our movement in the United States took shape and grew up on his ideas without his physical presence, without even any communication in the first period. Trotsky was exiled and isolated in Alma Ata when we began our struggle for Trotskyism in this country in 1928. We had no contact with him, and for a long time did not know whether he was dead or alive. We didn't even have a collection of his writings. All we had was one single current document - his "Criticism of the Draft Program of the Comintern." That was enough. By the light of that single document we saw our way, began our struggle with supreme confidence, went through the split without faltering, built the framework of a national organization and established our weekly Trotskyist press. Our movement was built firmly from the very beginning and has remained firm because it was built on Trotsky's ideas. It was nearly a year before we were able to establish direct communication with the Old Man.

So with the sections of the Fourth International throughout the world. Only a very few individual comrades have ever met Trotsky face to face. Yet everywhere they knew him. In China, and across the broad oceans to Chile, Argentina, Brazil. In Australia, in practically every country of Europe. In the United States, Canada, Indochina, South Africa. They never saw him, but the ideas of Trotsky welded them all together in one uniform and firm world movement. So it will continue after his physical death. There is no room for doubt.

Trotsky's place in history is already established. He will stand forever on a historical eminence beside the other three great giants of the proletariat: Marx, Engels, and Lenin. It is possible, indeed it is quite probable, that in the historic memory of mankind, his name will evoke the warmest affection, the most heartfelt gratitude of all. Because he fought so long, against such a world of enemies, so honestly, so heroically, and with such selfless devotion!

Future generations of free humanity will look back with insatiable interest on this mad epoch of reaction and bloody violence and social change-this epoch of the death agony of one social system and the birth pangs of another. When they see through the historian's lens how the oppressed masses of the people everywhere were groping, blinded and confused, they will mention with unbounded love the name of the genius who gave us light, the great heart that gave us courage.

Of all the great men of our time, of all the public figures to whom the masses turned for guidance in these troubled terrible times, Trotsky alone explained things to us, he alone gave us light in the darkness. His brain alone unravelled the mysteries and complexities of our epoch. The great brain of Trotsky was what was feared by all his enemies. They couldn't cope with it. They couldn't answer it. In the incredibly horrible method by which they destroyed him there was hidden a deep symbol. They struck at his brain! But the richest products of that brain are still alive. They had already escaped and can never be recaptured and destroyed.

We do not minimize the blow that has been dealt to us, to our movement, and to the world. It is the worst calamity. We have lost something of immeasurable value that can never be regained. We have lost the inspiration of his physical presence, his wise counsel. All that is lost forever. The Russian people have suffered the most terrible blow of all. But by the very fact that the Stalinist camarilla had to kill Trotsky after eleven years, that they had to reach out from Moscow, exert all their energies and plans to destroy the life of Trotsky-that is the greatest testimony that Trotsky still lived in the hearts of the Russian people. They didn't believe the lies. They waited and hoped for his return. His words are still there. His memory is alive in their hearts.

Just a few days before the death of Comrade Trotsky the editors of the Russian Bulletin received a letter from Riga. It had been mailed before the incorporation of Latvia into the Soviet Union. It stated in simple words that Trotsky's "Open Letter to the Workers of the USSR"14 had reached them, and had lifted up their hearts with courage and shown them the way. The letter stated that the message of Trotsky had been memorized, word by word, and would be passed along by word of mouth no matter what might happen. We verily believe that the words of Trotsky will live longer in the Soviet Union than the bloody regime of Stalin. In the coming great day of liberation the message of Trotsky will be the banner of the Russian people.

The whole world knows who killed Comrade Trotsky. The world knows that on his deathbed he accused Stalin and his GPU of the murder. The assassin's statement, prepared in advance of the crime, is the final proof, if more proof is needed, that the murder was a GPU job. It is a mere reiteration of the lies of the Moscow trials; a stupid police-minded attempt, at this late day, to rehabilitate the frame-ups which have been discredited in the eyes of the whole world. The motives for the assassination arose from the world reaction, the fear of revolution, and the traitors' sentiments of hatred and revenge. The English historian Macaulay remarked that apostates in all ages have manifested an exceptional malignity toward those whom they have betrayed. Stalin and his traitor gang were consumed by a mad hatred of the man who reminded them of their yesterday. Trotsky, the symbol of the great revolution, reminded them constantly of the cause they had deserted and betrayed, and they hated him for that. They hated him for all the great and good human qualities which he personified and to which they were completely alien. They were determined, at all cost, to do away with him.

Now I come to a part that is very painful, a thought which, I am sure, is in the minds of all of us. The moment we read of the success of the attack I am sure everyone among us asked: couldn't we have saved him a while longer? If we had tried harder, if we had done more for him - couldn't we have saved him? Dear comrades, let us not reproach ourselves. Comrade Trotsky was doomed and sentenced to death years ago. The betrayers of the revolution knew that the revolution lived in him, the tradition, the hope. All the resources of a powerful state, set in motion by the hatred and revenge of Stalin, were directed to the assassination of a single man without resources and with only a handful of close followers. All of his coworkers were killed; seven of his faithful secretaries; his four children. Yet, in spite of the fact that they marked him for death after his exile from Russia, we saved him for eleven years! Those were the most fruitful years of his whole life. Those were the years when he sat down in full maturity to devote himself to the task of summing up and casting in permanent literary form the results of his experiences and his thoughts.

Their dull police minds cannot know that Trotsky left the best of himself behind. Even in death he frustrated them. Because the thing they wanted most of all to kill-the memory and the hope of revolution-that Trotsky left behind him.

If you reproach yourself or us because this murder machine finally reached Trotsky and struck him down, you must remember that it is very hard to protect anyone from assassins. The assassin who stalks his victim night and day very often breaks through the greatest protections. Even Russian tsars and other rulers, surrounded by all the police powers of great states, could not always escape assassination by small bands of determined terrorists equipped with the most meager resources. This was the case more than once in Russia in the prerevolutionary days. And here, in the case of Trotsky, you had all that in reverse. All the resources were on the side of the assassins. A great state apparatus, converted into a murder machine, against one man and a few devoted disciples. So if they finally broke through, we have only to ask ourselves, did we do all we could to prevent it or postpone it? Yes, we did our best. In all conscience, we must say we did our best.

In the last weeks after the assault of May 24, we once again put on the agenda of our leading committee the question of the protection of Comrade Trotsky. Every comrade agreed that this is our most important task, most important for the masses of the whole world and for the future generations, that above all we do everything in our power to protect the life of our genius, our comrade, who helped and guided us so well. A delegation of party leaders made a visit to Mexico. It turned out to be our last visit. There, on that occasion, in consultation with him, we agreed upon a new campaign to strengthen the guard. We collected money in this country to fortify the house at the cost of thousands of dollars; all our members and sympathizers responded with great sacrifices and generosity.

And still the murder machine broke through. But those who helped even in the smallest degree, either financially or with their physical efforts, like our brave young comrades of the guard, will never be sorry for what they did to protect and help the Old Man.

At the hour Comrade Trotsky was finally struck down, I was returning by train from a special journey to Minneapolis. I had gone there for the purpose of arranging for new and especially qualified comrades to go down and strengthen the guard in Coyoacan. On the way home I sat in the railroad train with a feeling of satisfaction that the task of the trip had been accomplished, reinforcements of the guard had been provided for.

Then, as the train passed through Pennsylvania, about four o'clock in the morning, they brought the early papers with the news that the assassin had broken through the defences and driven a pickax into the brain of Comrade Trotsky. That was the beginning of a terrible day, the saddest day of our lives, when we waited, hour by hour, while the Old Man fought his last fight and struggled vainly with death. But even then, in that hour of terrible grief, when we received the fatal message over the long-distance telephone: "The Old Man is dead"-even then, we didn't permit ourselves to stop for weeping. We plunged immediately into the work to defend his memory and carry out his testament. And we worked harder than ever before, because for the first time we realized with full consciousness that we have to do it all now. We can't lean on the Old Man anymore. What is done now, we must do. That is the spirit in which we have got to work from now on.

The capitalist masters of the world instinctively understood the meaning of the name of Trotsky. The friend of the oppressed, the maker of revolutions, was the incarnation of all that they hated and feared! Even in death they revile him. Their newspapers splash their filth over his name. He was the world's exile in the time of reaction. No door was open to him anywhere except that of the Republic of Mexico. The fact that Trotsky was barred from all capitalist countries is in itself the clearest refutation of all the slanders of the Stalinists, of all their foul accusations that he betrayed the revolution, that he had turned against the workers. They never convinced the capitalist world of that. Not for a moment.

The capitalists - all kinds - fear and hate even his dead body! The doors of our great democracy are open to many political refugees, of course. All sorts of reactionaries; democratic scoundrels who betrayed and deserted their people; monarchists, and even fascists - they have all been welcomed in New York harbor. But not even the dead body of the friend of the oppressed could find asylum here! We shall not forget that! We shall nourish that grievance close to our hearts and in good time we shall take our revenge.

The great and powerful democracy of Roosevelt and Hull wouldn't let us bring his body here for the funeral. But he is here just the same. All of us feel that he is here in this hall tonight - not only in his great ideas, but also, especially tonight, in our memory of him as a man. We have a right to be proud that the best man of our time belonged to us, the greatest brain and strongest and most loyal heart. The class society we live in exalts the rascals, cheats, self-seekers, liars, and oppressors of the people. You can hardly name an intellectual representative of the decaying class society, of high or low degree, who is not a miserable hypocrite and contemptible coward, concerned first of all with his own inconsequential personal affairs and saving his own worthless skin. What a wretched tribe they are. There is no honesty, no inspiration, nothing in the whole of them. They have not a single man that can strike a spark in the heart of youth. Our Old Man was made of better stuff. Our Old Man was made of entirely different stuff. He towered above these pygmies in his moral grandeur.

Comrade Trotsky not only struggled for a new social order based on human solidarity as a future goal; he lived every day of his life according to its higher and nobler standards. They wouldn't let him be a citizen of any country. But, in truth, he was much more than that. He was already, in his mind and in his conduct, a citizen of the communist future of humanity. That memory of him as a man, as a comrade, is more precious than gold and rubies. We can hardly understand a man of that type living among us. We are all caught in the steel net of the class society with its inequalities, its contradictions, its conventionalities, its false values, its lies. The class society poisons and corrupts everything. We are all dwarfed and twisted and blinded by it. We can hardly visualize what human relations will be, we can hardly comprehend what the personality of man will be, in a free society.

Comrade Trotsky gave us an anticipatory picture. In him, in his personality as a man, as a human being, we caught a glimpse of the communist man that is to be. This memory of him as a man, as a comrade, is our greatest assurance that the spirit of man, striving for human solidarity, is unconquerable. In our terrible epoch many things will pass away. Capitalism and all its heroes will pass away. Stalin and Hitler and Roosevelt and Churchill, and all the lies and injustices and hypocrisy they signify, will pass away in blood and fire. But the spirit of the communist man which Comrade Trotsky represented will not pass away.

Destiny has made us, men of common clay, the most immediate disciples of Comrade Trotsky. We now become his heirs, and we are charged with the mission to carry out his testament. He had confidence in us. He assured us with his last words that we are right and that we will prevail. We need only have confidence in ourselves and in the ideas, the tradition, and the memory which he left us as our heritage.

We owe everything to him. We owe to him our political existence, our understanding, our faith in the future. We are not alone. There are others like us in all parts of the world. Always remember that. We are not alone. Trotsky has educated cadres of disciples in more than thirty countries. They are convinced to the marrow of their bones of their right to victory. They will not falter. Neither shall we falter. "I am sure of the victory of the Fourth International!" So said Comrade Trotsky in the last moment of his life. So are we sure.

Trotsky never doubted and we shall never doubt that, armed with his weapons, with his ideas, we shall lead the oppressed masses of the world out of the bloody welter of the war into a new socialist society. That is our testimony here tonight at the grave of Comrade Trotsky.

And here at his grave we testify also that we shall never forget his parting injunction - that we shield and cherish his warrior-wife, the faithful companion of all his struggles and wanderings. "Take care of her," he said, "she has been with me many years. Yes, we shall take care of her. Before everything else, we shall take care of Natalia.

We come now to the last word of farewell to our greatest comrade and teacher, who has now become our most glorious martyr. We do not deny the grief that constricts all our hearts. But ours is not the grief of prostration, the grief that saps the will. It is tempered by rage and hatred and determination. We shall transmute it into fighting energy to carry on the Old Man's fight. Let us say farewell to him in a manner worthy of his disciples, like good soldiers of Trotsky's army. Not crouching in weakness and despair, but standing upright with dry eyes and clenched fists. With the song of struggle and victory on our lips. With the song of confidence in Trotsky's Fourth International, the International Party that shall be the human race!